Spinal Cord Injury From A Mother’s Perspective By Laquita Dian. Dian is the Co-Founder and President of C.O.R.E. Centers, as well as the mother of Spinal Cord Injury Specialist, Aaron Baker

It’s been over 18 years since my son’s accident, and this is one of the truths I’ve held close since then: when faced with a catastrophic injury, it is wrong for medical professionals to state dire, hopeless prognoses. Hope for improvement must be left intact. I encourage the declared absolutes to be focused on the list of secondary complications that will occur if one does not actively pursue a wellness protocol. Hope is medicine. Hope provides a positive outlook one can focus on during the journey towards recovery.

Recovery is a nebulous term, as you never really know what type of recovery you may have, until you try. It is completely true, however, that the pursuit of recovery itself is the best medicine for a hopeful outcome, whatever that may be. Knowing that you are doing everything possible, everyday, provides satisfaction, willingness to continue and a sense of peace with what is. It’s the power of possibility that counts.

Nothing in my accomplished life prepared me for the morning of May 27, 1999 when I walked into an Intensive Care Unit to find my 20-year-old son alive only because of life support machines of every type.

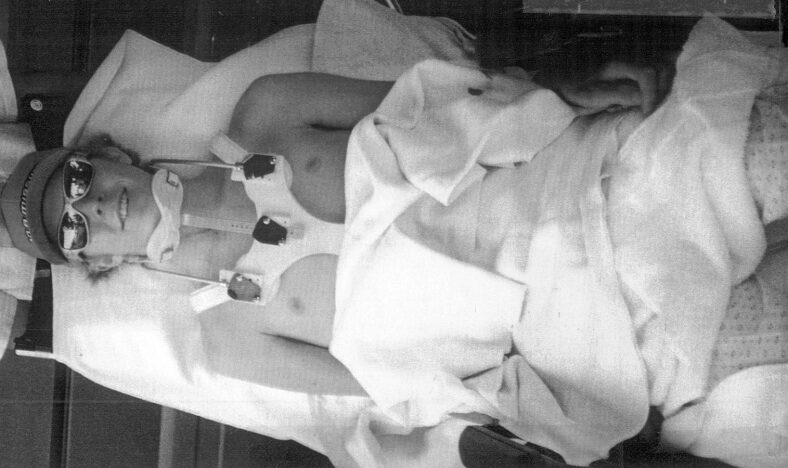

He had broken his neck and the resulting spinal cord injury had completely paralyzed him from the shoulders down. A ventilator provided breathing, a feeding tube provided for nutritional intake, a heart and oxygenation monitor showed what we couldn’t actually visualize ourselves, a hemovac intubated on the front of his neck for fluid and blood drainage at the surgical site which stabilized his three fractured cervical vertebrates, and IV tubes forced different medicines into his fragile body.

My son was lying in a full-body cut-out bed, with all of his extremities strapped down so nothing moved as the bed rotated from side to side to prevent fluids filling his compromised lungs. This was a horrifying, shockingly surreal site, and as I took in the scene, I struggled to breathe. My heart was shattered within the confines of my chest.

When a nurse came in to tell me my fifteen minutes was up, I snapped back to the reality that now belonged to my son and myself. ICU visiting hours allowed for fifteen minutes at a time, every few hours. Although the nurse’s voice sounded as though it was coming through a long reverberating tunnel, it became very loud and strict as she explained that the waiting room was down the hall and it was time for me to go and wait there until the next visit was allowed.

This command brought me into an acute awareness and I very adamantly and assuredly told her I was not leaving my son under any circumstance. I asked her to simply please bring me a chair, otherwise I would sit on the floor. While she objected, I countered by telling her to go obtain a court order to force me out.

A few minutes later, a surgical nurse came in to let me know the neurosurgeon was in the conference room to explain the details and extent of damage my son had sustained. The first words I heard were that the surgery went well, however Aaron would have a one in a million chance of regaining any function, including the ability to feed himself again.

This impossible prognosis shot me up out of my chair shouting, “No, no, you are not talking about my son. I want to meet again tomorrow to discuss the procedure and not the prognosis.” I quickly rushed out of the conference room, slamming the door. I found myself reeling and sliding down the hallway wall. I was overcome with nausea, tears streaming down my cheeks, with a piercing pain which felt as though I was dying myself.

As I sat in a dazed heap, immobilized, a sudden spark of sanity set in, making me realize that if I did not pull myself together, that doctor’s prognosis from that day would be absolutely true. This realization forced me up off the floor and I immediately went to Aaron’s room to begin directing his care.

I asked my sister to go buy a CD player and a number of different CDs of meditation music and sounds of nature to transform the room into a healing environment. I requested that his hospital room doors be kept shut: I would meet medical professionals in the hall to instruct them to not give Aaron any type of negative information regarding the severity of his injury, specifically the grim prognosis they provided to me. I wanted them to say they did not know, that anything was possible with dedicated work.

The music never stopped during our six-month hospital stay. I say “our” because true to my initial statement of not leaving without a court order, I indeed did not. Our process was not learning to adapt to the injury, as the hospital’s rehabilitative system encourages and facilitates; instead we worked for improvement, utilizing every nanosecond, every moment in rehabilitation to move forward.

Being proactive assisted tremendously with my ability to cope, knowing without a doubt that if I did not take this kind of action, once again that the initial prognosis would be true. I passionately believed that if I could be Aaron’s arms, his hands, his legs and alleviate even one of the devastating myriad of frustrations he was experiencing, this would allow him to conserve his limited energy and to channel that energy to his rehabilitation.

Catastrophic injury is not discriminating nor does it only completely alter the injured one’s life. Every family member, every friend is affected severely.

My daughter was 18 years old when her beloved brother was injured. She felt as though she lost not only her brother, but me as well. Aaron’s critical situation, which appeared permanent, required dedicated focus, daily consistent work and a newly limited lifestyle; freedoms, spontaneity and finances were now limited.

I had to immediately retire my career and my new career became Aaron’s recovery. His sister would vacillate between devastation and anger that so much had been taken from all of us, and then to horrifying guilt that she still had her ability, while her brother did not. I often refer to the family of those that suffer a catastrophic injury as the silent, invisible casualty.

Aaron is truly one in a million. Through our determination, teamwork and focus, he has regained the ability to not only feed himself, but also to walk, ride a bike and recover many physical abilities that are often taken for granted.

The future of recovery will come by way of collaboration between scientific research and continued rehabilitative exercise. I resonate with the passion for a Spinal Cord Injury cure and the pursuit for a bright future of possibility. This is why I’ve dedicated my life to this purpose, something much larger than myself and which benefits the greater good.

“We can, we must, we will.”

-Laquita Dian

For more information, see related articles and spinal cord injury resources here:

I have progressive MS and I find it hard sometimes to have a positive attitude. How do you reach out to others?

I have progressive MS and I find it hard sometimes to have a positive attitude. How do you reach out to others?