And hospitals say everyone who needs a hospital could suffer as a result.

Ohio’s hospitals report they are at or near capacity right now because of a surge in COVID patients, as medical professionals overwhelmingly continue to recommend COVID vaccines and masks. Even if the makeshift hospitals set up at the start of the pandemic were stood up again, that won’t solve the problem. There are not enough doctors, nurses, and other staff to care for the influx of patients who are trending younger, are sicker, and in nearly all cases, unvaccinated.

Just a couple of months ago, Shekela McCarty was a nurse at a Columbus hospital.

“It started out where we got all the support of the community. And then it turned into kind of a distrust between the healthcare community and then our community. It became where we felt more threatened as health care workers. And I was tired of feeling like that. We’ve seen a lot of death, a lot of very sick individuals. We’ve had to have some very difficult heart to hurt conversations with family. And it takes a toll on you mentally after a while,” McCarty says.

McCarty says the toll was so great that she quit and now works for an insurance company. Other nurses and medical staffers are quitting and retiring…..exacerbating a shortage of medical care professionals.

“Everybody at the hospital seems to be dealing with belligerent, aggressive family members of people who don’t believe in the reality of COVID. They get upset about restrictions and they want treatments that are not evidence-based or have evidence that they’re ineffective. But, you know, they get frustrated because they hear something, they read something on Facebook. Oh, this helps. And then they want it. And that’s very frustrating,” Klatt says.

Dr. Gregory Lam works in a hospital in a small town near Columbus. He says doctors and nurses are putting their own health and sometimes their lives on the line daily. He recently saw it first hand when a medical team was trying to keep a COVID patient alive.

“I saw our nurses, respiratory therapists, working valiantly to resuscitate him. In some cases, their own PPE was falling off because they were so vigorously pumping on his chest and trying to intubate him. In some cases, our respiratory therapists were literally inches from his face, which was viewing secretions. And I knew that they were exposing themselves to the coronavirus. Now everyone was vaccinated. But we know that these breakthrough infections occur, and they knew that, too. But yet they still did their job to try to save this man’s life. And I knew that they wouldn’t stop until they were told to stop. But this weighs on us because, on one hand, we took an oath to help people. But on the other hand, we know that we’re potentially jeopardizing our families, we’re potentially jeopardizing our own lives. And that’s tough,” Lam says.

It’s not just hospitals that are feeling the stress right now. Dr. Michael Joseph works with a group that operates urgent cares in Central Ohio where many people are going to get COVID tests being requested for employers, traveling or entry into special events. He says the front office staff often takes the brunt of it.

“I’ve had people front desk people in tears that I’ve had to help counsel here and try and regroup. And I’ve had to talk to patients who were inappropriate with our staff and help them calm down as well,” Joseph says.

The shortage of health care workers right now is real in clinics, along with big and small medical facilities. Dr. Alan Rivera with the Fulton County Health Center says as nurses retire or move to other jobs, COVID patients, who he says are largely unvaccinated, are increasing.

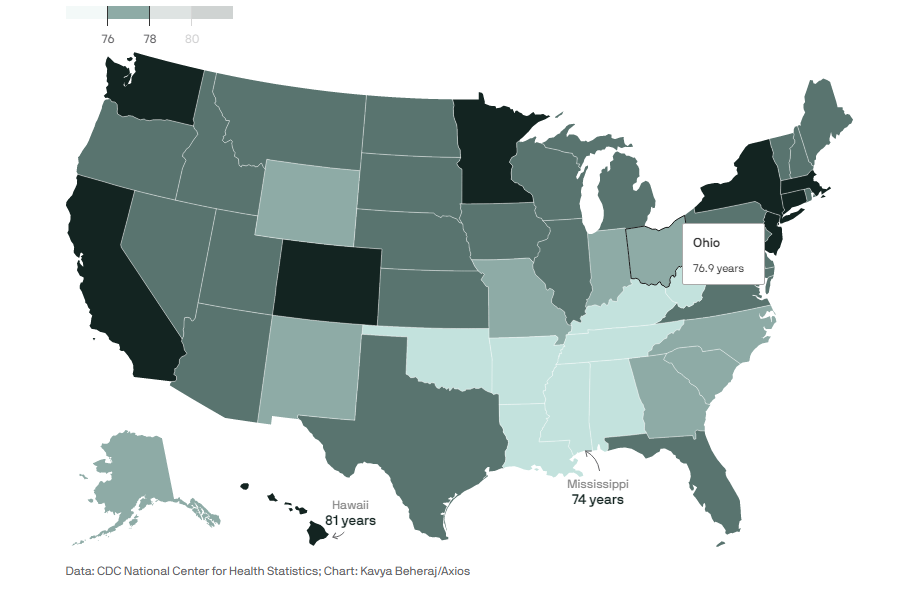

“So, in June and July, I didn’t see any COVID patients. August, September. Now the majority of my senses in the hospital, our COVID patients, and they are younger anywhere from 30 to 50, is what we’re seeing here in northwest Ohio,” Rivera says.

Rivera says COVID patients are very sick and tend to stay in hospitals longer than the average patient. He says that means patients with other problems like heart attacks or those who have been in accidents sometimes cannot get immediate treatment.

Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff says the Delta variant is six times more contagious than previous versions of the virus. Earlier this week, Vanderhoff issued an ominous warning, saying unvaccinated people are likely to catch COVID at some point. “If you are young and unvaccinated, it’s not probably a question of when not if, you get COVID 19,” Vanderhoff says.

Southern Ohio has been hit the hardest so far. Dr. Suzanne Bennett of the University of Cincinnati Health Center says it’s not just staff that’s in short supply. She says equipment is being stretched too.

“This week alone, I have received approximately ten to 15 calls from doctors in our community, our state, and the surrounding Tristate area requesting ECMO for their dying patients. These patients are anywhere from the ages of 18 to 60, but actually this time the majority are in their 20s to 40s, as you outlined, often otherwise healthy, these patients are healthy this time around and the vast majority are, however, we have in a space and we don’t have the additional nurse. At this time we have to put them on the waiting list, something we learn to do during our last surge of COVID when we had to turn multiple patients away because of resources. And too many times than not, these patients die at the other hospital waiting for this critical resource,” Bennett says.

Hospitals in some cities have had to go on what’s known as “emergency bypass” recently. That means emergency squads cannot deliver patients to that facility while it is in that status. Last week, during a five-hour period, all of the major hospitals in the Toledo area were on emergency bypass.

Columbus nurse Jen Hollis says it’s tough for those on the front lines of patient care.

“I think of the pressure that it weighs on that family member hoping to just be able to if I just get to this place, maybe they’ll have a chance. And they’re waiting for days and days and weeks or not even getting that chance anymore because they, unfortunately, they expire. And that’s just not. You know, we’re just looking at their names from bed board, there their patient I’m waiting. But this is somebody’s mom or somebody’s dad or somebody’s brother,” Hollis says.

Terri Alexander, a nurse at Summa Health in Akron, breaks down as she describes what she’s facing daily.

“We’ve got patients in their thirties, and now we’re dealing with women who are pregnant and they’re in there and it’s just a sad situation that we’re dealing with. And I think everybody here is emotionally exhausted and just really affected personally at work and at home. It’s hard to come in with the staffing levels that we have with the shortages of equipment that we have and play that balancing game that we play every day with beds, with equipment,” Alexander says.

There isn’t much evidence that medical workers are quitting because medical systems are requiring COVID vaccines. A poll earlier this year found 3 in 10 are considering leaving because of the danger, stress, and frustration. And a study this spring in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested a significantly increased suicide risk for nurses, who are the largest component of the health care workforce. Those who look out for the mental health of medical workers say it’s important to remember the impact of the pandemic on those subjected to the worst parts of it every day.

Read original article by Jo Jingles | The Statehouse News Bureau