Sometimes, as paradoxical as it sounds, more intervention means more freedom.

When my son, Charlie, was three, I walked into his special needs preschool one breezy spring afternoon to pick him up after his physical therapy as per usual. Except nothing about this moment was usual. When I rounded the corner to his class, I glimpsed his back, his curling blond hair, his little hands resting on the arms of an impossibly small black wheelchair. I hadn’t known they even made wheelchairs that small. But there it was and there he was. He looked comfortable. He looked happy. His therapist pivoted him towards me and he grinned and my heart lifted.

This, I told myself, was it. This would bring the freedom we’d been hoping for. With wheels of his own, he could navigate the halls and the stations of his classroom—kitchen set, science set, puzzles, books, the world was his for the choosing.

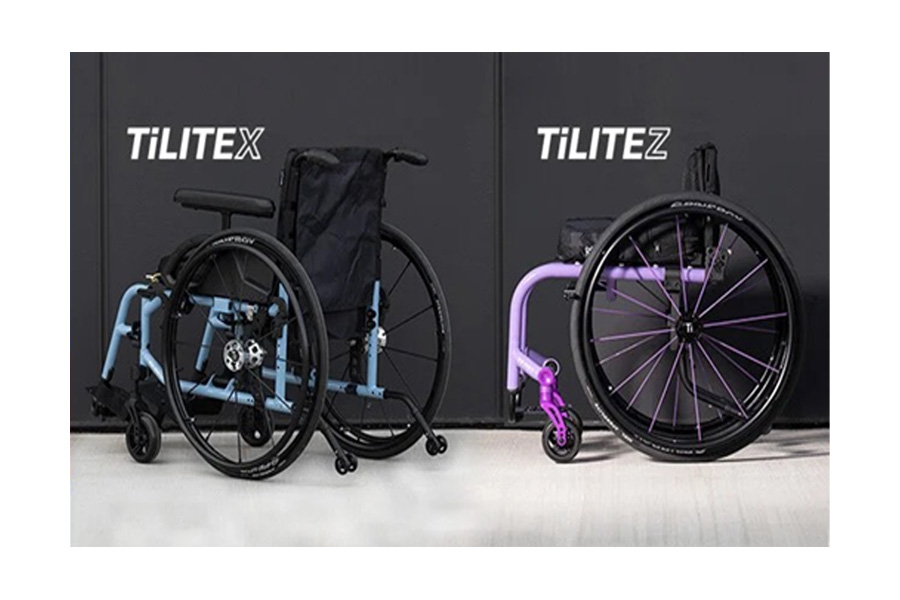

And he did roll. Sort of. He wheeled a few feet when no one was looking. Or, because he preferred using his left hand rather than both, he turned in slow circles…a graceful solo dance. And in this way, the years passed. We waited for the proficiency we were sure was right around the corner. We moved from that trial wheelchair to one specially designed for him. We practiced in the driveway and our cul-de-sac. We practiced in our church atrium. We practiced in the corridors of the mall, before the stores opened, when the halls felt like empty runways waiting for take-off. Except he never did take off. Not really. He halfheartedly rolled this way and that, but it never became intentional or natural or easy. By the time he was six, he had almost stopped trying altogether, content to be pushed by an adult or a classmate or his siblings.

Except Charlie wasn’t really content and I knew it. He wanted to go places, but had long ago assumed it would have to be under someone else’s power. I refused to make such assumptions. And so, on a similar spring day, with kindergarten looming, I walked into his preschool once more to watch him try out a power chair. It was black and purple and retro chic, as much as a three-hundred-pound motorized wheelchair can be retro chic.

And at first it was like watching the world’s worst game of Pacman. He would push the gearshift and steer himself directly into a wall or a corner or, hilariously, a closet. Reverse was tricky and made me wish for the warning beeps installed in buses and garbage trucks.

Stay on the cautious end of optimistic, I told myself. Better not get your hopes us, as you did with the manual chair, in case it doesn’t work out.

But something was different now. And it wasn’t all in my head. He did progress. And when he took that great leap off the diving board into kindergarten, he did find his own in that purple and black retro chair. He is now confident, to the point of obstinacy, in his ability to get himself where he needs to go. No, he’s not perfect at this driving business quite yet, but he’s getting there under his own power.

I know more medical equipment, more assistive technology, more therapy can feel like a step back, a reverse on the milestones when all you want to do is leap forward. But it can also be the leap. You never know when that one thing can create a door for your child where you once only saw a dead end.