Malnutrition is an imbalance between nutrients required and nutrients actually taken in. This imbalance results in deficits of energy, protein or micronutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, that may negatively affect growth and development in children. Both overnutrition and undernutrition are included in this definition.

- Overnutrition is associated with obesity and resulting chronic disease. An estimated 17% of U.S. children and adolescents between 2 and 19 years of age are obese (body mass index above the 95th percentile).

- Undernutrition can mean either not consuming enough nutrients to support normal growth and development or not being able to use nutrients consumed because of acute or chronic illness. It is not known how many U.S. children are undernourished but data suggests that 1 in 10 households with children struggle to obtain enough food.

About Pediatric Undernutrition

Pediatric undernutrition is estimated to contribute to approximately 45% of all child deaths world-wide. Historically, this has been considered an issue of developing nations but more recently has been recognized in the U.S. in the setting of acute or chronic illness.

Most at risk are the nation’s special needs children and those who are hospitalized or chronically ill. Children with special health care needs are more likely to develop persistent emotional, behavioral, physical and developmental conditions that affect their nutrient intake. They should be assessed for malnutrition on a regular basis by health care professionals, including doctors, nurses and dietitians.

Classifying Pediatric Malnutrition

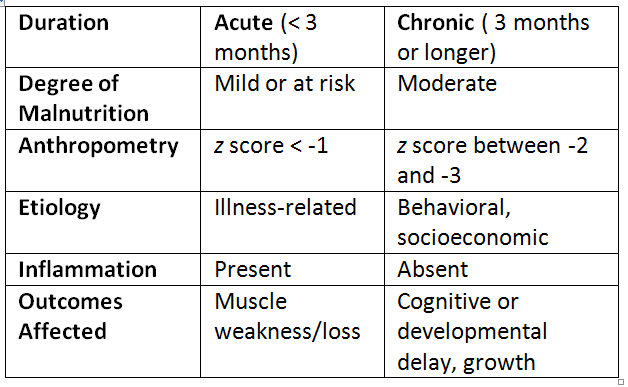

Accurate diagnosis of malnutrition in children has traditionally been difficult. A group of physicians, nurses, dietitians and pharmacists have identified indicators to classify malnutrition among children 1 month to 18 years old (see table below). These parameters are separated into acute (severe, sudden and short-term) and chronic (becomes more severe over the long term).

In children, acute illness often affects weight while chronic illness may stunt normal growth and development. An acute illness lasting for less than three months may cause mild malnutrition or put a child at risk for malnutrition. Usually, a degree of inflammation is present and weakness or loss of muscle occurs.

Chronic illness lasting three months or longer may cause moderate or severe malnutrition resulting in cognitive or developmental delay. Long-term food insecurity or behavioral and emotional problems are considered potential causes of this type of malnutrition.

Z scores are used to compare a child’s weight, height and age to what is considered normal in this population.

Measuring and Monitoring Nutrition Status

Nutrition status can be quantified using one or a combination of a few different methods. Some of them are below.

Handgrip Strength

Handgrip strength is a method used to identify and monitor nutritional status by measuring muscle strength, which tends to respond quickly to changes in nutrition status caused by illness. A child is asked to squeeze a device that measures the strength of the hand and forearm muscles. This method can predict postoperative complications, length of hospital admission and likelihood of readmission.

Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

Mid-upper arm circumference is another method to assess nutritional status. Measurement of a certain part of a child’s arm can detect changes in muscle and fat mass. It can also be compared to measurements from normal healthy children in certain age groups. One way to ensure that this method is accurate is to have the same trained person take repeated measurements over time.

Growth and Growth Velocity

- Growth is defined as an increase in size and maturation.

- Growth velocity is the rate at which a child grows in weight or height over time.

The rate of increase in length or height reflects a child’s nutritional status over time. Weight loss or lack of weight gain can indicate malnutrition. While most children can recover from acute injury or illness and catch up to normal weight and growth, chronic illness or ongoing environmental factors can prevent normal growth from occurring.

Follow-Up

Once pediatric malnutrition is identified, children should be routinely monitored by a pediatrician and a registered dietitian specializing in pediatrics. Factors that contribute to undernutrition, such as acute or chronic illness and socioeconomic or behavioral circumstances should be addressed on an ongoing basis. There is no consensus on how often an undernourished child should be followed and frequency will depend on the individual.

Reference:

Becker P, et al. Consensus Statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Indicators Recommended for the Identification and Documentation of Pediatric Malnutrition (Undernutrition). Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2015;30(1): 147-161.

This information is intended for educational purposes only. Consult your child’s health care professional for advice on your child’s health and nutritional status.