Reviewed and updated September 6th, 2024.

Pressure injuries (AKA pressure ulcers) impact an estimated 2.5 million patients each year in U.S. acute care facilities[1]. While some pressure injuries are unavoidable, most can be prevented, and an effective way to prevent a pressure injury is by moving and changing position frequently.

The current accepted “guideline for care” is to turn patients every two hours[2]; however, there is much more involved in finding the right solution for your patient. The frequency of turns should be individualized to your patient based on such factors as:

- Patient’s tissue tolerance

- Level of activity and mobility

- General medical condition

- Overall treatment objectives

- Skin condition

- Comfort[3]

Testing a patient’s tissue tolerance involves documenting the time it takes the skin to redden over bony prominences. The test is a step-by-step procedure, where the caregiver gradually increases the amount of time the patient is left in the same position until reddened skin is detected. Once that time has been established, set the turn frequency to 30 minutes less than the time interval.

In addition to determining the frequency of turn, you also need to move and reposition the patient using proper technique. First, when you reposition the patient, make sure that pressure is actually relieved or redistributed. Second, avoid positioning the individual on bony prominences with existing non-blanchable skin, which is an early sign of skin breakdown. Third, lift—don’t drag—the patient while repositioning. This will reduce damage to skin due to friction and shear.

Bed Positioning

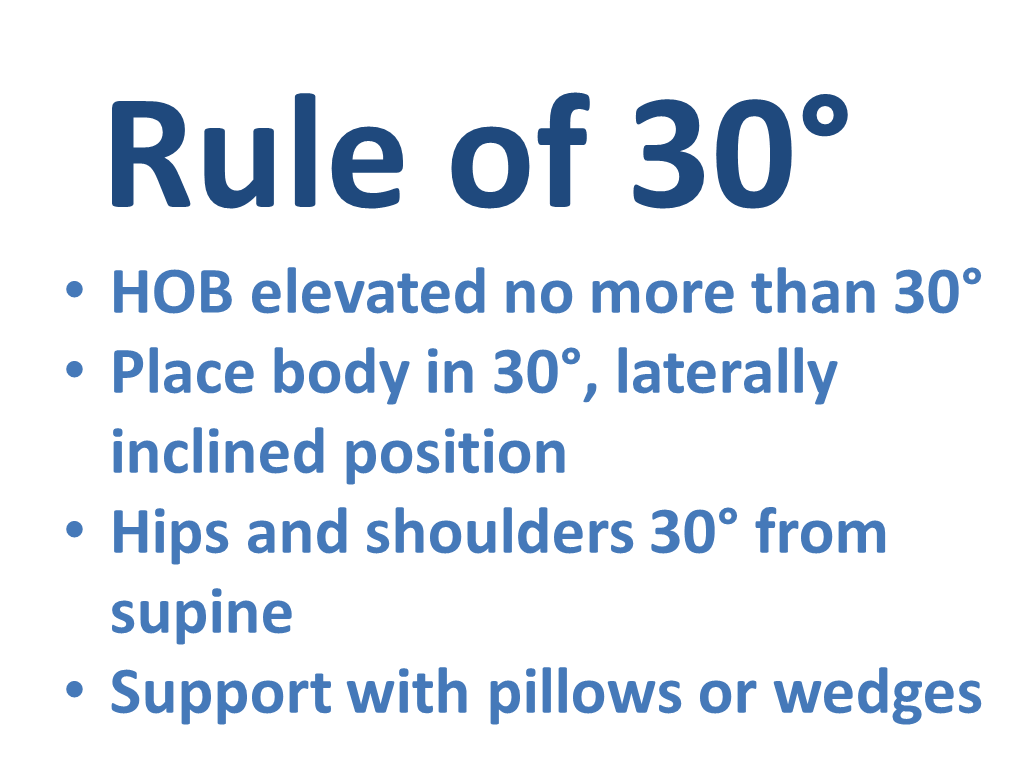

A good guideline for repositioning a bedridden patient is the “Rule of 30”[4]. The Rule of 30 means the head of the bed is elevated at no more than 30 degrees from horizontal and the body is placed in a 30-degree, laterally inclined position. In the laterally inclined position, tilt the patient’s hips and shoulders 30 degrees from supine, and use pillows or wedges to keep the patient positioned without pressure over the hips or buttocks.

Repositioning can be difficult. Here are some helpful step-by-step tips for repositioning:

Getting a patient ready

- Explain to the patient what you are planning to do so the person knows what to expect. Encourage the patient to help you if possible.

- Stand on the side of the bed the patient will be turning towards and lower the bed rail.

- Ask the patient to look towards you. This will be the direction in which the person is turning.

- Move the patient to the center of the bed so the person is not at risk of rolling out of the bed.

- The patient’s bottom arm should be stretched towards you. Place the person’s top arm across the chest.

- Cross the patient’s upper ankle over the bottom ankle.

If you are turning the patient onto the stomach, make sure the person’s bottom hand is above the head first.

Turning a patient

- Adjust the bed to a level that reduces back strain for you. Make the bed flat.

- Get as close to the patient as you can.

- Place one of your hands on the patient’s shoulder and your other hand on the hip.

- Standing with one foot ahead of the other, shift your weight to your front foot as you gently pull the patient’s shoulder toward you. Then shift your weight to your back foot as you gently pull the patient’s hip toward you.

You may need to repeat steps 3 and 4 until the patient is in the right position.

When the patient is in the right position

- Make sure the patient’s ankles, knees, and elbows are not resting on top of each other.

- Make sure the head and neck are in line with the spine, not stretched forward, back, or to the side.

- Return the bed to a comfortable position with the side rails up. Check with the patient to make sure the patient is comfortable. Use pillows as needed[5].

Seated Repositioning

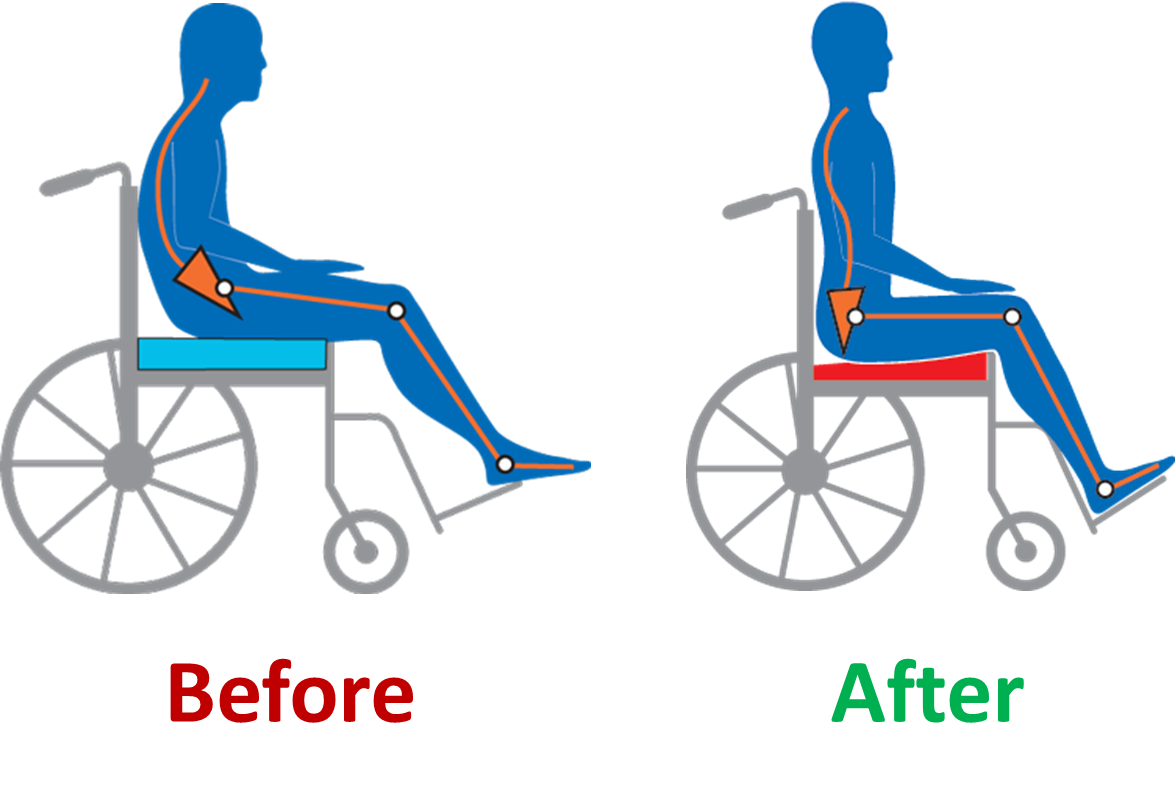

Seated patients need to be turned more frequently than bed-bound patients. Teach the chair-bound patient to shift his or her weight every 15 minutes. If the patient is unable to reposition, move the patient every hour. In addition, use a pressure redistribution cushion, which will distribute the weight of the body without impeding function or increasing potential for skin damage.

Credit: AliMed

When working with seated patients, ensure the equipment is properly fitted. Observe for the “hammock effect,” where a sagging seat causes a patient’s thighs to roll inward and expose the hips to pressure from the sides of the chair. Also, poor-fitting chairs can cause patients to slouch, which will lead to increased pressure on the buttocks, thighs and spine. Placing a cushion on a sagging seat will not fix the problem; you’ll need to replace the sagging seat with a solid seat that’s covered with an appropriate pressure-reducing cushion.

Mobilizing and repositioning bedbound and chair-bound patients is just part of the care to prevent the development of pressure injuries, and each patient will present different needs. Other factors, such as the patient’s nutrition, medical condition, skin condition, and tissue tolerance will also impact the treatment objective and patient outcome. Taking into account the whole picture will help yield better results.

[1] Padula, William V, and Benjo A Delarmente. “The National Cost of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries in the United States.” International Wound Journal, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7948545/#iwj13071-bib-0005.

[2] Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development (JRRD)

[3] National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. Emily Haesler (Ed.). Cambridge Media: Osborne Park, Western Australia; 2014.

[4] Wound Care Education Institute, 2015

[5] Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Health; 2023.

For more information about preventing pressure and treating pressure injuries, see related articles and resources here:

I think in 1C we do our best to make sure our patients don’t go home with pressure injuries. turn my patients every two hours but I think if continue our happy hour practice that will greatly help.