From the moment I open my eyes in the morning to my last yawn before bed, I live with whole body spasticity and reoccurring muscle spasms, resulting from my spinal cord injury. My body can feel like The Tin Man from the classic film, “Wizard of Oz.” Metaphorically, I feel as though my metal frame was left out in the rain to rust and is in desperate need of an oiling. Even though I can now initiate movement in all four of my limbs, my stiffness resulting from spastic paralysis and unintentional spasms can counteract most of all my intentional motion. This common secondary complication to spinal cord injury was very welcomed early in my recovery because even though my muscle contractions were involuntary, they were movement. I would visualize and connect my mind to the muscle during a spasm and try to work with the contraction, assisting in the movement. Today, however, increased spasticity can be the source of pain and frustration. In this first part of a two-part article, I describe spasticity, spasms, tone and clonus and how by understanding the cause and effect of these secondary conditions one can ultimately gain more control over an out-of-control body.

Spasticity, Spasms, Tone & Clonus

What is spasticity and spasm?

When you Google these terms, “spasticity” can simply be described as involuntary muscle stiffness, and “spasms” as involuntary muscle contractions. It is good to know that all the muscles in the body can be affected, but spasticity and spasms tend to predominantly affect the limbs or trunk. I describe my spastic muscles as feeling stiff like beef jerky: heavy and difficult to move. Sometimes my spasticity can be so severe that it can be very difficult to bend an arm or leg and in the morning I can experience full body spasms so severe that I’m nearly thrown out of bed (no joke!).

What is tone?

Muscle tone is described as the resistance felt when an arm or leg is moved or stretched. Normal tone occurs when an individual is relaxed and a health professional can bend and straighten a limb without difficulty. An increase in tone (like in my case, an increase in resistance to movement) can be due to spasticity, spasms and or changes in muscles, tendons and ligaments as a secondary result of the conditions mentioned above.

Do you know about clonus?

This involuntary, repetitive up and down movement (like the foot of a drummer) is observed as a constant tapping of the foot or hands as rhythmic, on/off muscular contractions and relaxations that tends to co-exist with spasticity. Some consider clonus as simply an extended outcome of spasticity and, in my case, it is a common, regular occurrence. Although closely linked, clonus is not always seen in everyone with spasticity. Clonus tends to not be present in people with significantly increased muscle tone, as the muscles are constantly active and therefore not engaging in the characteristic on/off cycle of clonus.

Important technical info

(Tip: Google this) Clonus results due to an increased motor neuron excitation, decreased action potential threshold and is common in muscles with long conduction delays, such as the long reflex tracts found in distal muscle groups (hands, feet, knees or spine) … Me!

I actually give a demonstration of my ability to control clonus by sitting in an upright position, lifting and dropping my leg onto the ball of my foot, triggering clonus in my foot which unintentionally bounces like I have had one too many espressos. Then, I describe how I focus my thoughts into my lower leg, sending a slow intentional signal to relax the muscles effectively stopping the spasm.

Why do these symptoms occur?

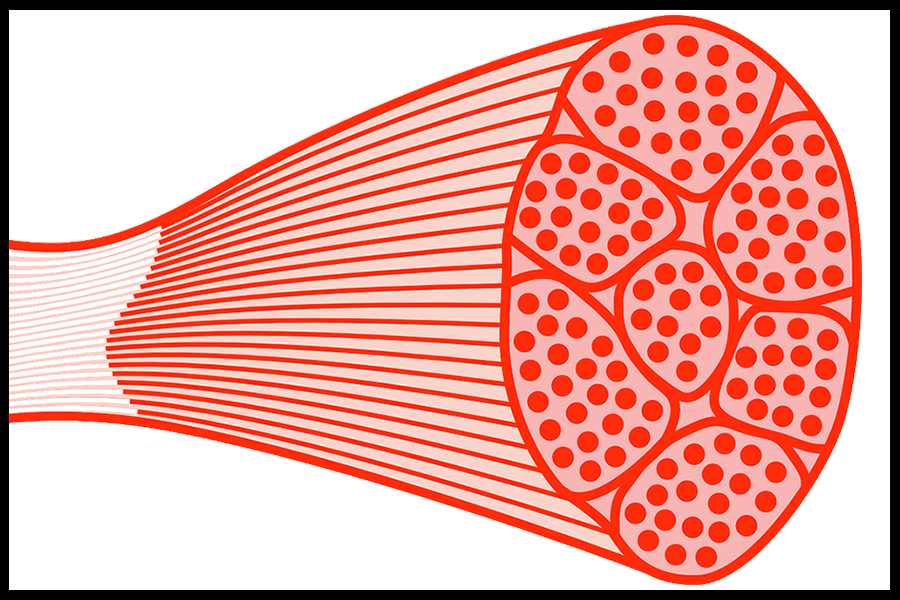

Watch out – technical jargon coming through! Nerve pathways that connect the brain, spinal cord and muscles work together to coordinate movements of the body. These pathways can be disrupted by a disorder of the central nervous system. Spinal cord injury, stroke or a central nervous system disease can all lead to loss of coordination and/or function of the muscles. In general, spasticity develops because of a change in the balance of signals between the brain and the muscles, leading to increased activity (excitability) in muscles. Meaning: receptors in the muscles receive messages from the nervous system, which sense the amount of stretch in the muscle and sends that signal to the brain. The brain then responds by sending a message back to the muscle to reverse the stretch by contracting or shortening which is called the stretch reflex. This reflex is important in coordinating normal movements in which muscles are contracted and relaxed, and keeps the muscle from stretching too far and tearing from the bone – this is the body’s way of protecting itself.

Understanding Triggers

Certain factors are known to exacerbate spasticity and spasms. Minimizing these can reduce spastic symptoms. The bottom line: the body and brain are not communicating well and a trigger is the body’s way of telling the brain something is wrong.

A few common triggers are:

- Urinary tract infections or retention

- Bowel impaction or constipation

- Red or broken skin/pressure areas

- Painful ingrown toenails

Pain and infection will most often aggravate spasticity. A less obvious trigger can be tight-fitting clothes or splints. In this case, the person they may be in massive discomfort and in need of relief but have no idea what is causing these feelings.

It’s not all bad

As I mentioned in the opening paragraph, I choose to use the involuntary contractions of my spastic condition as helpful assistance. Although my spastic body can be frustrating and sometimes further debilitating, I see the benefits of muscle tone, spasticity and intermittent clonus.

For one, I like to intentionally initiate clonus to stimulate blood circulation in my lower legs and feet. My blood tends to pool in my limb, so the on/off cycle of muscle contractions helps keep my blood pressure up and regulated. Second, my overall muscle mass is better maintained against atrophy because of consistent muscle tone. Third, my bone density is improved because of the forces applied by the muscles. Lastly, if I experience an increase in spasticity for no apparent reason, then I know my body is trying to communicate a distress signal like pain or infection that I am not aware of and calls for further investigation.

In the second part of this article, I will share my top ten tips and tricks for managing my sometimes “possessed” body. I discuss my method versus medications and how I make spasticity work for me, rather than against me. Stay tuned!

You can find Part 2 – How I Manage My Possessed Body here.

Do you have a question for Aaron Baker? Ask Aaron here!